‘People said I was ruining this company’: John Schoolcraft on the transformation of Oatly

Oatly OOH campaign in Shoreditch, London.

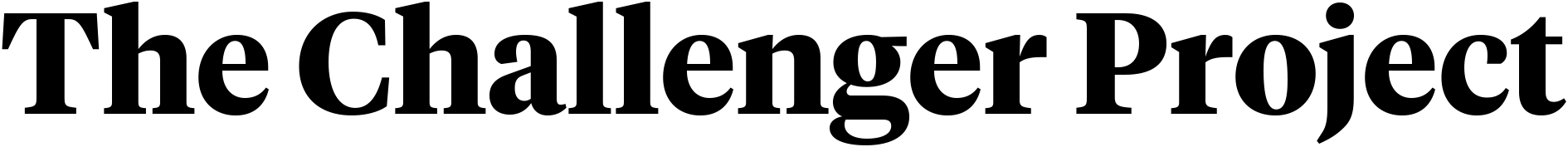

‘It tastes like sh*t.’ Maybe not the kind of praise that would tempt you to switch from cow’s milk to an oat alternative. This was a real comment from someone trying Oatly for the first time, which Oatly were brave enough to not only place on its packaging but also turn into an ad. John Schoolcraft is Creative Director and responsible for decisions such as these. In three years, under John’s direction, Oatly has transformed from a dull food processing company into a fearless challenger brand. The year following the re-launch, company annual revenues increased 100% reaching US$41m in 2016. [2022 update: $643.2m revenue]

What was the situation at the company before you joined in 2012?

John Schoolcraft, Creative Director of Oatly. Photo: Oatly.

The company actually started with quite an entrepreneurial ethos. It was founded by researchers at the University of Lund in the early 1990s when they discovered oats could provide a nutritional alternative to cow's milk. They saw an opportunity to cater for those who were allergic or had personal reasons to not drink dairy, so packaged it, put it on the shelves and Oatly was born.

As the company grew however, it turned into a something resembling a Proctor and Gamble out in the field. A small company of 50 employees, but behaving like a major multinational. Looking at computer data for how to do marketing for instance. I remember seeing an Excel spreadsheet that reported brand recognition at 70%, when the reality was less than 5% at the time. In terms of the brand, I used to say it looked like a Dutch multinational, just indistinguishable from anything else on the shelves.

How did you first get involved in the project?

Oatly’s packaging in 2012.

The board wanted someone who would shake things up and create an entirely new vision for the company. This wasn’t about redoing the logo. They wanted someone without a background in the food industry and all the baggage that would bring so hired Toni Petersson as new CEO. Toni and I have worked together for 15 years prior to Oatly so he called me and asked if I wanted to be involved. My first thought was maybe if we took the oats out we could do something cool with it. What I soon realised was, that although the brand was invisible, everything inside the pack was fantastic, and so the oats actually ended up becoming key to everything. I then started working in stealth, so just working with Toni on how we might turn this into what we called a lifestyle brand — not necessarily like a Red Bull, or Nike but a brand that would fit very naturally into people’s lives.

What was the inspiration that led you to the new positioning and finding a bigger purpose?

Toni Petersson, the reluctant CEO.

As in lots of conceptual development, we initially looked at the origins and roots of the brand. We recognised that if people drink our products, they’re doing something good for themselves in terms of their health but also for the planet in terms of the carbon emissions and land usage from production.

I grew up in the US where meat is part of every meal. Then when you work here, you see all the numbers, and the statistics, and the scientific reports, and you realise that animal-based eating is killing the planet and killing people. We knew we needed to do more than just sell a product, we needed to have a far bigger visionary ambition. So it really became about Oatly contributing to a plant based society, or for us to at least encourage steps in that direction.

Once decided on the new strategy, what was the first change you made?

We started with the packaging. It’s owned media and because we don’t have these US or UK size advertising budgets it’s really our main media. Usually, in the food industry, any change whatsoever made to the packaging would make the company very nervous that sales would dip. Brands will make slight tweaks so customers don’t get confused and the result is no one notices. We approached it differently, we just threw the old packaging out completely and were prepared to take the hit.

Oatly UK packaging 2016.

If you look at the dairy alternative packaging on shelves; the liquid is always shown, it usually pours from the right hand side, everything is colour coded to a pattern that exists in the design world. There are so many conventions. The aim was to get customers to pick it up out of curiosity so we intentionally made these look like we’d just made these in the basement at home. We thought that every side of the packaging there should be something interesting to read. The legal side on the back we refer to as the boring side. We know that once we’re in people’s hands, they read the copy, try us, and tend, in great numbers, to like the taste.

I remember Toni called the whole company together for a meeting, and we unveiled the new packaging. Someone stood up and said this was the worst, most childish packaging they had ever seen and asked me why I was ruining this company. People can react quite negatively to change, and for some of them, this just threatened their entire existence. The funny thing is those were sketches projected onto the wall. When we got things printed and people are sitting holding the packs, those same people told me how excited and proud they were.

How did you go about getting support for the change of strategy?

That was probably the most difficult thing. We had a company full of academics and scientists, people who are happy and really great at what they do, and we wanted to change into a lifestyle brand. We wanted everyone to work completely differently, becoming very fluid. We wanted to scrap the marketing department, scrap the role of product manager, and create an in-house creative team instead. We couldn’t just tell people that was the plan, it would have been impossible as real lives are being affected here. In order for us to make that change, we needed to have a platform we could share with everyone that would explain what we were doing and why. We created a wooden book and everyone got a copy. It contained conceptual development so people got a look and feel of what the brand could be. We also produced videos that accompanied the book that helped bring the new direction to life.

Without that book, people didn’t have anything to look forward to, and they didn’t have anything to complain about. The complaining was actually just as important. People would still say ‘this is crazy’, ‘why are we doing this?’, but in time it helped everyone really understand the direction and reach agreement. Four years later, all we’ve done is execute the book. If you start at Oatly today, you get the same book from 2012 and we haven’t changed a word. The key is not to just talk about making changes but actually get on and do them. We just set about implementing the changes, and then gave people all the time and help to understand them.

Oatly isn’t a brand afraid to speak its mind. How did that personality and tone of voice develop?

People are easily bored, so if someone writes something unexpected it tends to make people feel good. I’ve been a copywriter in the past and enjoy writing. At Oatly I write what I want at the time to make it interesting if I read it. There’s a lot of freedom here.

We ran a full-page ad in The Guardian called Bigfoot. It included a lot of our beliefs as a company; our view on what’s wrong with the current food farming system, on race and gender equality, on how the pursuit of profit without consideration for the planet should be considered a crime – these are some very political statements - brands don’t do that. But we find that as our beliefs are around nutritional health and sustainability, we’re able to talk quite honestly because we’re not bullshitting. I think that’s the key, people appreciate an authentic and honest brand. Even if a company is honest about the things it is not good at, it will just come off as being the type of person that people want to hang out with.

‘Be human and not a logo’ is a phrase in the strategy book and also here around the offices – what’s the problem with logos?

In a time when people weren’t able to distinguish brands, it became necessary to use logos to ensure recognition. But logos don’t talk. They’re boring. If a brand is relying on its logo in 2016 then it’s not doing its job as a brand. We have a logo of course, but we made it look irregular by splitting it up, we then added an exclamation point at the end because you’re not supposed to do that either. On some of our packages we’ve gone further and replaced the logo entirely with the words ‘Not Milk’ so we’ll have no logo on the pack. What’s important is what’s inside the company. We don’t really think of ourselves as a corporation. We’re real people working together to try to help other people get a good product. There’s an open dialogue.

You’ve described Oatly before as being a company that’s fearless when 90% of companies are scared shitless. How did you become fearless?

I’ve worked with Toni for a number of years. If I screw up with a campaign, it’s my fault and we discuss it. We’ve removed a lot of the fear and hierarchy that most companies have. We’re prepared to take few a calculated risks and that means we’ve become quite fearless. We were sued in 2014 by the Dairy Association, an organisation that exists to promote dairy products in Sweden. If you want to explain oat milk to someone, you first have to explain the concept of milk. It’s like an electric car. How would someone explain the concept of an electric car without first explaining the car? So we wrote some very direct copy that explained the differences between oat and dairy milk. Apparently that wasn’t legal. They claimed we had discredited milk so they filed a lawsuit against us.

Most companies would immediately back down, but because we felt we had just spoke the truth we published the entire 172 page lawsuit on our website and let the public decide. We had no idea what public opinion would be, but it quickly became a David versus Goliath situation where thousands of people began to support us because they could see it was a bully tactic. We then took a full page ad out in the morning papers that explained that we had been sued and why and suddenly the milk vs oat war is making headline news. We went from niche to mainstream in part because of that lawsuit so in one sense we were quite fortunate.

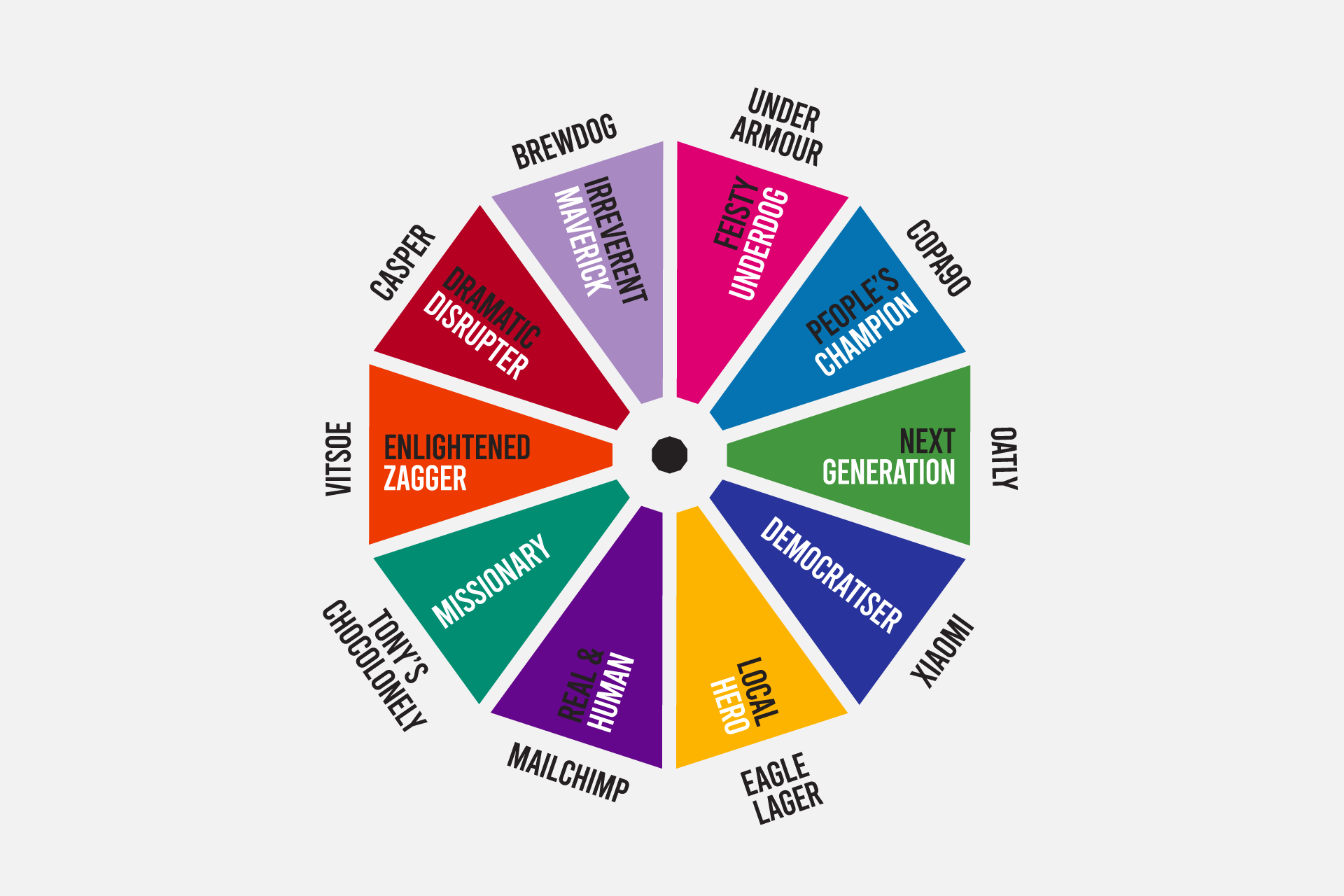

What do you think it means to be a challenger today?

Everyone wants to be a challenger brand, but I’m not sure if everyone really knows how much of a pain it is. It would be far easier if I just went to work, did my job, and then went home. Do we really want to work 18-hour days? Do I really want to put my personal phone number on the packaging? It means the newspapers are ringing you, you’re constantly under threat of getting sued. We’re going to have these issues to deal with as we grow. It’s very difficult. It’s all-encompassing. At the same time, if you’re not willing to stand up to the big boys and show a different way, you just get lost, you end up in the 90% of the companies that are scared shitless. You can feel the brands that really are challenger brands because they run a lot of risks. Both personal risks and corporate risks also.

“Everyone wants to be a challenger brand, but I’m not sure if everyone really knows how much of a pain it is.”

Being a challenger is having a mindset of realising you’re trying to change something, rather than be a challenger to be cool and help sell more products. Because consumers will be able to feel it. Of course, we want to sell our product, but we want to challenge the norms at the same time, and that’s bigger. If you can get that right, you’re going to sell a lot of product, and we need to sell the product so that can continue to do what we’re doing.

#3BitsofAdvice

John Schoolcraft on transforming a company culture

1. Take action, don’t just talk about change. Revealing the new packaging demonstrated the new direction to the company more than any words could.

2. Remove fear from the culture. Make people feel safe and secure enough to make the right decisions for the company.

3. Inspire the people who are working at the company to think that this time right now in their career is going to be the best period of their professional lives. No one is holding them back.